1.Cassandra and Paul can you tell us a bit about yourselves? Where were you brought up and educated?

Paul:

It’s a strange thing, but although Cassandra and I are different ages and live in different cities, we discovered some months after meeting that we were both born in Rose Park Hospital in Adelaide, on the traditional Country of the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains. I mention this because my first eight years in Adelaide were important to me and if Cassandra were older, we may have been able to collaborate very much earlier—although I suspect I was a rather difficult child, so that may not have been such a good idea! As a boy I was shy, rather introverted, also extraverted and fascinated by school—especially mathematics. However, after my two years at Mitcham Infant School and one year at Mitcham Primary School in Adelaide, and once my family moved to Perth, Western Australia—where my father had taken a job in the fledgling Politics Department at the University of Western Australia—my educational experiences assumed something of a downward trajectory.

This may have been largely due to the idiosyncrasies of my developing personality. I was easily bored, had poorly developed study habits and was, I suspect, too inclined towards a kind of early melancholic reflectiveness for someone of my age. However, I’ve always thought that the light of the Adelaide Hills and of the Adelaide suburbs climbed inside me in those first eight years and has constituted an abiding landscape for my poetry ever since; and that my childish melancholia meant that even early on I wanted something I could do for myself alone—something to shape and dwell in. Eventually that ‘something’ became poetry and, as I tried to learn to write it, I went to Hollywood Senior High School and then to the University of Western Australia—where I completed an honours degree and a PhD. I continued to live in Perth until my wife, Michelle and I and our two daughters moved to Canberra in my early thirties.

Cassandra:

As Paul mentions, we were both born in Adelaide. I would have liked to have known him then because I suspect his quixotic nature would have been appealing (Paul says he doubts that). I spent my early years on the Magic Mountain waterslides in Glenelg—I especially loved Glenelg because the word is a palindrome and as a kid that seemed ‘magical’. I moved to Melbourne and was educated at an all-girls Catholic secondary school. It did not have a glamorous name like Hollywood High and unlike Paul, I never missed a day of school. I participated in so many extra-curricular activities that they wouldn’t all fit on my report card and I was probably proudest of playing Rizzo in the School Production of Grease and being voted Cheerleading Captain in Year 11 and 12. Subsequently, I went to the University of Melbourne and completed: Bachelor of Arts (Hons) with double honours in English and History; a Master of Arts in Literature (on Nabokov’s Lolita), a Graduate Diploma of Education and a PhD in Literature (on Gwen Harwood) under the supervision of Chris Wallace-Crabbe.

2. When did you realise you were interested in reading and writing poetry?

Cassandra:

Cassandra Atherton

My grandmother read to me from the time I was born, so words were always under my skin. My favourite birthday gift was a Roget’s Thesaurus when I was eight years old and I used to carry it around and offer my family synonyms when they were talking to me—which must have been incredibly annoying! I also gave myself a word of the day between the ages of eleven and thirteen, which I tried to use as often as possible over the designated twenty-four hours. I am an only child, so I guess this is what I did to amuse myself. I’ve always like memorising things and poetry was something I would recite in my childhood, enjoying the feeling of rhyme. My nana loved the bush poets, so I grew up on their rhymes and I used to recite The Man from Snowy River at four years old. It was only in secondary school that my Literature teacher, Mary Holmes, introduced me the joys of poetry beyond Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson. I didn’t have a poetry calling like Paul, who I think resolved to be a poet in the womb!

Paul:

Like many children, I read books of children’s verse as I was growing up. I also enjoyed fairy tales and various other forms of prose, but verse and poetry exerted a particular early fascination. This was probably because of the rhythmic life and music of its language; its formality; its occasional silliness; its inventiveness; and its sheer ‘thinginess’. Then, at the age of eleven, I decided I would write poetry and be a poet. I don’t know what I was thinking then because, although my mother had read a small amount of adult poetry to me—and expressed admiration for it—I had no real idea of what I was getting myself into. I simply had the (marvellous to me) idea that I would be a poet regardless of every other possible vocation—although for a short period I also retained a nascent interest in mathematics and the philosophy of logic (I know that’s rather idiosyncratic primary school fare). And I’ve never changed my mind about poetry. I’ve always thought of poetry as what I do—not as ‘work’ but as an occupation. Even though I have had what might be called a ‘career’ outside of poetry, my love of poetry has driven many of my life decisions and vocational choices.

3. Who were your influences?

Paul:

My parents influenced my poetry in various ways. They both had a feel for writing, and a more general interest in art and culture. I grew up believing that cultural matters were vitally important and that an understanding of what is broadly called the ‘humanities’ was part of being educated. In terms of other writers, influences on my poetry are hard to pin down because I read fairly widely over many years before I managed to write what I thought of as a decent poem. However, as with most writers, influences of diverse kinds jiggled away in me for some time while I was trying to learn my craft. For instance, as a teenager I read translations of ancient Greek poetry, including Sappho; and Hamlet; the English Romantics (rather haphazardly); some poems by T.S. Eliot and so on. As an undergraduate at university, and subsequently, I read many more poets’ work, including W.B. Yeats, Emily Dickinson and various poets from the Penguin Modern European Poets series. I also read more deeply in Australian poetry, including the work of writers such as John Shaw Neilson and Judith Wright. I read ancient and contemporary Asian poetry in translation and for a period was fascinated by a few of the Tang Dynasty poets, such as Du Fu and Li Bai. Poetry by Denise Levertov, Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, Robert Lowell, Rosemary Dobson, Gwen Harwood, Mark Strand, Seamus Heaney and Robert Bly all struck me at various times—and I remember hearing Mark Strand read at the University of Western Australia in (I think) the 1970s. Overall, I enjoy the work of many, many writers—and that includes novelists. Some nineteenth-century and twentieth-century novels, in particular, remain among my favourite works—Middlemarch and Tess of the d’Urbervilles are examples. However, although I read fairly widely, I went through an extended period where I thought I hadn’t found my poetic ‘voice’ while at the same time feeling that the work of other poets didn’t speak for me. Mind you, during this period I wrote copious amounts of poetry—more than a thousand mostly short lyrics—and eventually burned almost all of them in my late twenties. It was only after that that I sensed a more decisive way forward.

Cassandra:

My literature teacher instilled in me an enduring love of Shakespeare, Donne, Keats, Browning, Emily Brontë (although I was secretary of the ‘Anne Brontë Appreciation Society’ at school), Hardy, Tennyson, Dickinson, William Carlos Williams, cummings, Harwood and the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. My obsession with Nabokov’s Lolita began at this time, too—such beautiful and poetic prose. I’ve also been influenced by ballet and contemporary dance (including tap, with its amazing syncopation) as I used to teach, examine and choreograph dance.

4. How do ideas for poems occur to you?

Paul:

Ideas for my poems mostly come unprompted, sometimes in the form of a word or phrase; or a rhythm; or a sense of something inchoate that’s forming in language. Or an idea may come from reading (not necessarily poetry), or watching television, or from what somebody says. In one sense, ideas arrive fairly indiscriminately—but I guess this is a process of encountering something that, as it were, tunes in or provokes a potential poem. Or sometimes a poem arises from a particular preoccupation I have. Poetry has its own rhythms and life and I believe poets should be grateful for any poetic visitations that occur.

Cassandra:

I get mini-obsessions and my prose poems grow from these. The first sequence of prose poetry I wrote in my late teens (published under a pseudonym—thank goodness!) was formed from my obsession with chandeliers and then I moved onto cherries and wrote an inordinate number of prose poems on cherries. Now I think my obsessions form important intertexts in my prose poems. In my book Exhumed my intertexts are references to some of my favourite classic novels, poetry and films. Currently, I’m working through my enduring love of the Pre-Raphaelites and their muses. I’m a curious person who loves research, so I like to indulge my obsessions by reading and researching until I’m living and breathing them—that’s what gets me thinking poetically.

5. When did you become interested in writing prose poems?

Paul:

I had no interest in writing prose poems until 2014. In that year I began writing short pieces of rather fragmentary prose fiction and I also began to exchange emails with Cassandra about prose poetry after we met at a symposium. As we chatted, I soon became intrigued by her prose poetry, and by prose poetry more generally—after having spent most of my life believing I would never write a prose poem (indeed, I’d never given prose poetry much thought and would not even have professed to understand how it worked). So, this was partly a happy moment of synchronicity because, just as I felt some of my writing was beginning to fragment, I met a very fine writer who worked with a fragmentary form, providing an example for me. I set off in my own prose poetry directions and began to read more prose poetry. Cassandra and I also embarked on a research project connected to national and international prose poetry, which eventually led to the publication of the Anthology of Prose Poetry in Australia by Melbourne University Press and the publication of Prose Poetry: An Introduction in America by Princeton University Press—both released in late 2020. I suspect that if Cassandra hadn’t got me interested in the form (she’s a very persuasive advocate) I may never have started writing it or researching in the area. So, I owe her a significant debt, and for six years—since November 2014—prose poetry has been the main form of poetry I’ve written.

Cassandra:

In primary school I wrote fragments and scraps of things on grocery dockets and backs of envelopes, which I didn’t realise at the time was an early form of my prose poetry. I still have some of them in childish handwriting, written in blue pencil (the only thing we were ‘allowed’ to write with at primary school until we got our grey lead pencil licence). I regret never really having a poetry mentor because it took me a long time to connect my writing to the prose poetry tradition—right through university, I was told I wasn’t a ‘real’ poet because I didn’t write lineated poetry. My prose poetry partnership with Paul, which started in late 2014, was incredibly significant as he wanted to write scholarship about prose poetry as well as prose poems, something which had never really occurred to me and which has had a profound impact on my work. Also, when we first met, I suspected Paul was a bit of a literary snob, so I was thrilled that he took the prose poetry form to heart and embraced the little bricks of poetry to which I was devoted! Paul would email me brilliant prose poems from Canberra, Rome (did he tell you he was at the B.R. Whiting studio in Rome for a year?), Madrid, Tokyo and Dublin, which also renewed my interest in my own creative practice—pushing the boundaries of the prose poem in literal and figurative ways. Paul also started the International Prose Poetry Project which has built an inspiring and supportive community of prose poets. Ultimately, I think Paul will always return to his first love—the tradition of lineated lyric poetry—it holds something mysterious for him that he is drawn to, but I’m a prose poetry lifer!

6. What attracted you to this form?

Paul:

When I started writing prose poetry it seemed exactly the form I needed at the time. It was as if I had a lot to write about that only prose poetry would accommodate—subjects that were somehow unsuited to lineated poetry. Taking up the writing of prose poems released a store of energy and creativity and, in a way, it seemed a kind of blessing—as if something I’d unknowingly been waiting for had arrived. It is such a wonderful challenge to write poetry in sentences and paragraphs; to search for the kind of figurations, condensations, tonalities and rhythms that allow prose to function well in poetic terms.

Cassandra:

I love the way the prose poem’s cramped rectangle puts words under pressure and I adore its galloping, breathless pace that is occasionally interrupted with a slow, stealthy moment.

7. You’ve recently co-edited Anthology of Australian Prose Poetry. What is prose poetry?

Cassandra and Paul:

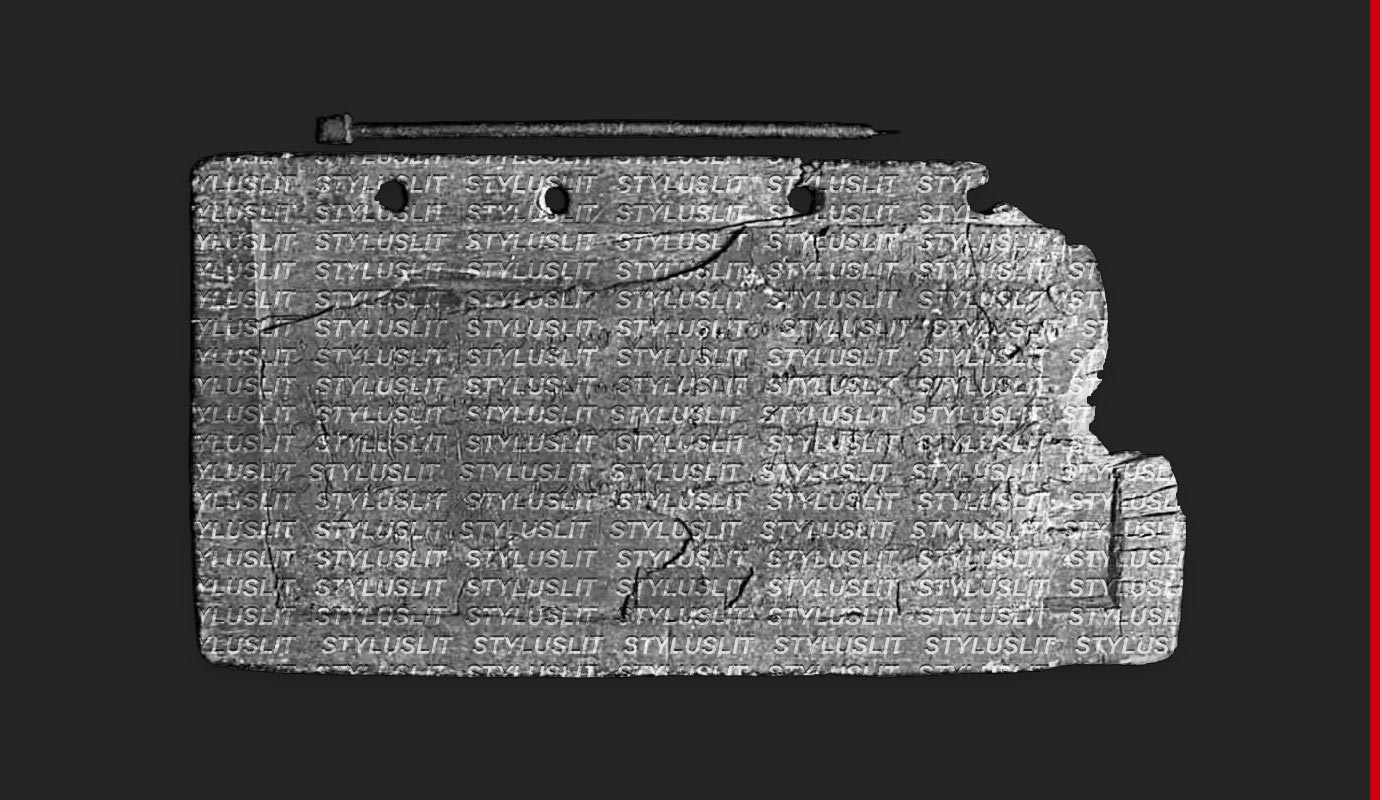

Prose poetry is notoriously hard to define—as, for that matter, is lyric poetry unless one is satisfied with broad generalities—and we’ll echo here some of the remarks we make in the introduction to the Anthology of Australian Prose Poetry. There is no real consensus on what makes a prose poem, but we believe that prose poetry differs from the more general category of poetic prose because it’s pithier and more condensed. Prose poems are usually fragmentary and brief and many prose poems occupy one page (or less), allowing the reader to swiftly gain a visual impression of the whole work. In such instances, especially where prose poems are fully justified, there may be some visual tension connected to the work’s appearance—almost as if, to repurpose an insight of Steven Monte’s, there’s an invisible fence around it. While fully justified prose poems are usually rectangular and box-like they may, alternatively, have a ragged or serrated right margin. However, in most cases, prose poetry sentences wrap at their margin rather than being lineated.

Michael Benedikt suggests prose poetry ‘is a genre of poetry, self-consciously written in prose, and characterised by the intense use of virtually all the devices of poetry’ and we’d add that prose poems are not primarily driven by narrative; that many prose poems gesture towards ideas, topics or concerns that exist outside the particular narratives they provide. Prose poems are typically fragments, resisting closure. And, as a part of their condensations of language, prose poems emphasise the connotative, the evocative and the ambiguous. Prose poetry also frequently speaks sideways—alluding, for example, to other literary or artistic works or referring, often ironically, to established literary conventions. Reading prose poetry is often a fairly rapid experience because of the brevity of works, but this experience may also be drawn out because poetic language has the capacity to slow the reader’s apprehension of time and to thicken or congest language’s movement.

8. How does it differ from microlit or flash fiction? Does it matter?

Cassandra and Paul:

The distinction between microlit or flash fiction and prose poetry matters a great deal because they belong to different genres—one is fiction and the other is poetry. Poetry works primarily through the generation of secondary, or figurative, meanings and associations; it often seeks out the ineffable and it tends to inhabit what Jonathan Culler refers to as ‘a special “now” … of poetic enunciation’. Carrie Etter has stated that ‘successful flash fiction almost always has some semblance of a narrative arc, even if it’s simply the protagonist facing a conflict and responding to it … whereas in prose poems any narrative is in the service of an overall idea that the poem circles or inhabits’. Ian Seed comments, ‘at the end of a piece of flash fiction you feel satisfied in some way, at the end of a prose poem you feel more like a dog barking at the shape of air’. In other words, while many prose poems exploit narrative techniques, they do so for poetic ends, so that the primary satisfaction in reading a prose poem derives not from the unfolding of narrative but from the suggestiveness of its language, which speaks of unquantifiable issues.

9. Would you call it a hybrid genre?

Cassandra and Paul:

We would say that prose poetry is a hybrid literary form rather than genre, in the general sense that it uses the mode of prose for poetic ends. Mind you, as far back as the bible (and even further back) prose has been used for poetic purposes. However, especially in the late twentieth- and early twenty-first centuries there has been a widespread embrace of apparently hybrid or new literary forms. Examples include the prose poem, the lyric essay, novels that largely dispense with narrative, fictocritical works, poetic memoir, and epistolary works written as poetry. There are also works that demonstrate what might be called a multivalent hybridity—such as graphic novels, which include prose poems. The prose poem is one of a number of kinds of literature that possess the characteristics, or use the techniques, of more than one established literary form or mode.

10. What were you looking for when you made your selection for the anthology?

Cassandra and Paul:

We were primarily looking for impressive individual prose poems as well as trying to build a truly representative selection of Australian prose poems from the 1970s to the present day—nearly fifty years of writing, and much of it buried in out-of-print poetry volumes and journals. In doing this, we also wanted to represent the various strands of Australia’s complex prose poetry landscape as fairly as possible—something that’s easy to say and hard to do, given that there are so many fine writers of prose poetry in this country. We each read a lot of prose poetry and selected works we liked, sometimes debating the merits of various prose poems, while also locating works that were historically important. We noticed early on that many fine Australian prose poems were by women and we ended up publishing more prose poems by women than by men. We also wanted the selection of works to represent a broad range of contemporary concerns and for some works to speak in the vernacular as well as in more ‘literary’ language—one of prose poetry’s strengths is its capacity to accommodate divergent speaking voices and registers. We were also aware that Australia has yet to fully address its colonial past and history of Indigenous dispossession, and that the prose poetry we selected ought to reflect this important issue, as well as the complex, multicultural makeup of Australia’s population.

11. Finally, are you working on anything at the moment?

Cassandra:

I’m editing two anthologies with Paul—Alcatraz: An International Anthology of the Short Form for Life Before Man publishers and an Anthology of Australian and New Zealand Poetry for the American publisher, MadHat Press. I’m also writing scholarship on dark poetry and a book of prose poetry on the atomic bomb in Hiroshima.

Paul:

I’m continuing to write prose poems and lineated poems, but perhaps in a rather undirected way, as I wait to see where they might take me. And I’m undertaking some academic research, too, continuing to pursue my interest in what poetry is and does.

Anthology of Australian Prose Poetry is published by Melbourne University Press.